Most Americans celebrate the Fourth of July, but not all. This year, some are calling for an economic blackout. The Women’s March is hosting a “Free America Weekend,” calling on citizens to liberate themselves from a political system where billionaires behave like kings. While many native tribes salute Indian veterans on Independence Day, others remember how for decades the approach of an American flag was not a good omen. The Fourth has always evoked mixed reactions, particularly within the black community.

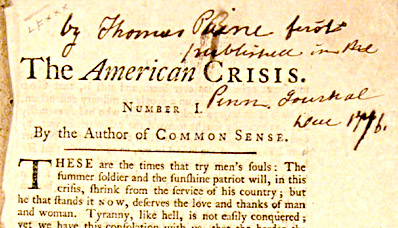

In 1852, Frederick Douglas delivered a fiery address asking “What To the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” At that time, three and a half million African Americans were considered human property. As a black man born into bondage on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Douglas found the festivities galling.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery.

These many years later, the question still resonates. Why celebrate? Perhaps because the Revolution was a multiracial win.

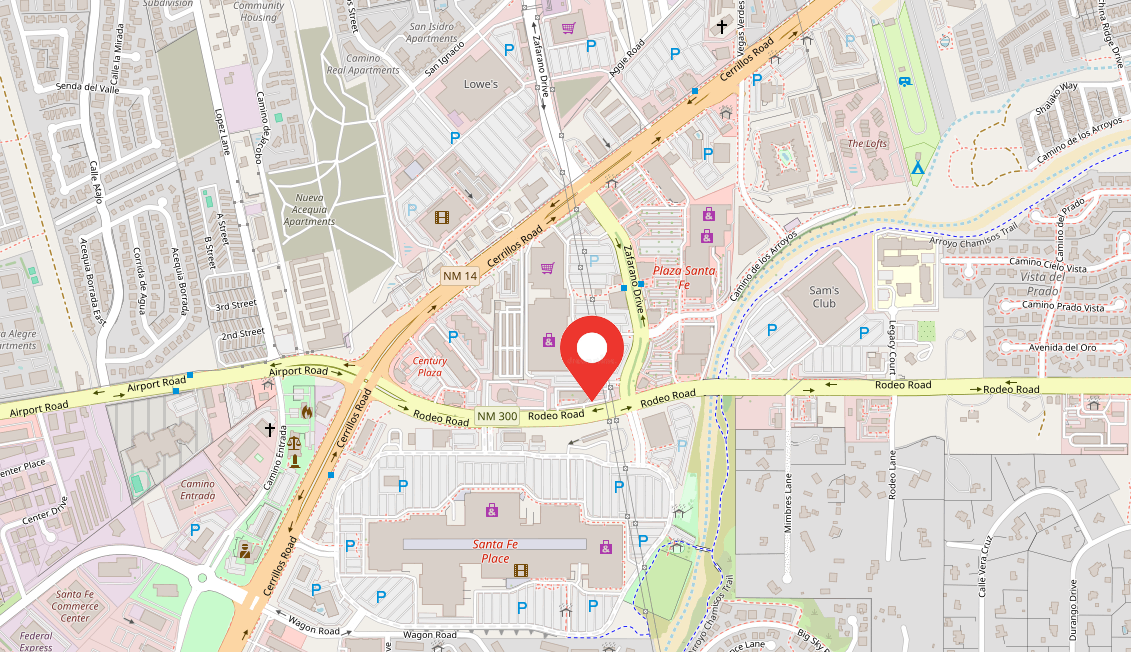

Indivisible Santa Fe is creating a library of people’s personal videos, where they react to their own fresh reading of the Declaration of Independence. After you read this post, learn more and add yours!

First, there was Bunker Hill. Because muskets were so inaccurate in those days, the Continentals were given the command, “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” In the melee that followed, the redcoats were savaged. A quarter of all the British officers who died during seven years of warfare fell in that single encounter. One of those shot through the brain was the British major John Pitcairn, killed by a former slave named Peter Salem. Indeed a study for the National Park Service found that one hundred and three of the American soldiers in that battle were men of color.

You may have learned in your high school history that Harry Truman was the first U.S. President to integrate the armed forces. Actually, George Washington was. All told, over 5000 African Americans served in uniform during the Revolution. Blacks were there at every major engagement, at Valley Forge, at Trenton, at Yorktown.

Rhode Island was the first and only colony to offer slaves complete emancipation in return for putting on a uniform. Yet other colonies offered their own inducements to serve. The pay was the same for black and white recruits. Continental dollars might not be worth much. But with the money, some slaves were able to buy their own freedom, or to purchase their loved ones out of bondage.

Some colonies restricted African Americans to non-combat functions, like fife and drum, understandably reluctant to put guns into hands where the barrels might be turned back on their former overseers. But fife and drum paid more than ordinary infantry, probably because they were hazard duty. Fifers were in the front lines, where they were signalmen. Drums told the troops when to advance, flank right, or stand fast. The musicians carried daggers to counter the bayonets that were deadlier than the flintlocks of that era. And in the heat of battle, evidence suggests that regardless of regulations, every man who could wield a weapon did his part.

Black soldiers absorbed the ethos of their compatriots. The lines about “self-evident truths” and “inalienable rights” became part of their moral vocabulary, echoed in pleas for their own full equality. Without knowing it, they became Lockean liberals, convinced that human relations rested upon a social contract, and that no man could deprive another of liberty without the first’s consent. In the famous painting of “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” for example, you spot one dark face among the crew toiling at the oars. That face belonged to Prince Whipple, born in Africa and transported to the Americas. Prince served in the Continental Army alongside his master. But in 1779, in the midst of the conflict, two years before he became a free man, he and nineteen other slaves petitioned the New Hampshire legislature in language that could have come from Thomas Jefferson or Ben Franklin, noting:

God of Nature gave them Life and Freedom, upon the Terms of the most perfect Equality with other men, That Freedom is an inherent right of the human Species, not to be surrendered, but by Consent, for the Sake of social Life; that private or public Tyranny and Slavery, are alike detestable to Minds conscious of the equal Dignity of human Nature …

Men like Prince Whipple were not just armed with muskets. They were armed with ideas that were every bit as powerful and in some ways even more explosive. Soldiers of color who had fought and prevailed against the mightiest empire on earth, walked and talked with a new confidence in themselves, inferior to no one.

In her book Standing in Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution published by the University of Oklahoma Press, scholar Judith Van Buskirk observes that before 1760, very few Americans questioned the institution of slavery. It was a fact of life, like the weather. People might not always like it, but no one believed they had any agency or could do anything about it. Slavery was a piece of the social landscape, background noise like death and taxes. But in the space of a generation, something happened. “By 1790,” she observes, “the northern states had put slavery on the road to extinction. The Constitutional Convention heatedly debated the role of slavery and representation. Abolition societies and aid societies sprang up in the north and south. What happened between 1765 and 1790? The American Revolution. After twenty years of talking about natural rights, equality and freedom had made it such that the institution of slavery would never more be part of the monotonous course of daily life.”

It would take generations to see the effects. It would take the American Revolution and the Civil War. It would take the Thirteenth Amendment. It would take mass movements and organizations and popular uprisings. It would take Montgomery and Selma and Black Lives to pass the torch forward. The flame of freedom faltered at times. It seems to flicker now, as our nation copes with white nationalists, with Proud Boys and hate groups, with police murders and resurgent racism. America has never fully embodied its promise of equality. But none of this should keep us from marking our Independence Day.

Frederick Douglas in 1852 acknowledged as much.

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men,, too, great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory....

I do not despair of this country.

I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from "the Declaration of Independence," the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions …

Those institutions are fragile, always in danger, and always in need of reform. So protest if you like. Boycott. Practice your right of free speech and freedom to assemble. Our nation began in protest. And the best way to celebrate that fact is to work for justice. Don't let the sacrifice of those Revolutionary black patriots be in vain.

Because America’s is an unfinished revolution, a revolution in progress, a revolution with a long way to go but with a notable beginning. Learn your history and then earn your history. Fly your flag right side up or upside down or not at all, but know why you’re doing it. Educate yourself. We have no need to bury or renounce or censor our past, nor any need to romanticize or gloss over it. For all its imperfections, it’s a heritage worth celebrating.

Indivisible Santa Fe is creating a library of people’s personal videos, where they react to their own fresh reading of the Declaration of Independence. Learn more and add yours!