August 5th marked the one-year anniversary of the overthrow of Sheikh Hasina, who for 15 years ruled Bangladesh as a paranoid autocrat.

I lived in Bangladesh for 24 years, having co-founded two non-profits working on advocacy for health and environment, which I still help run. I moved to Santa Fe only six months before Hasina’s regime crashed. Having followed the crisis and successful overthrow closely, I have some thoughts and observations to share, especially since Bangladesh doesn’t tend to garner much international attention.

In 2018, when a bus ran over and killed two young students, a mammoth student protest followed about the danger children and youth faced, daily, moving about the streets. The students had specific demands for safer roads in an environment where pedestrians (the majority) tend to be treated like the underclass and car drivers (a tiny minority) like royalty. The protests, focused as they were on road conditions, seemed pretty innocuous, but Hasina was not amused. She struck back harshly, attacking the students and ordering the police to beat up and arrest a popular photo journalist, Shahidul Alam (a wonderful man who, among other things, taught yoga at our regular car-free street events in Dhaka).

That attempt at intimidation had limited effect. International pressure eventually led to Alam’s release from jail and some symbolic attempts at addressing the students’ demands.

The next major demonstrations began in June of 2024, when university students protested quotas for government jobs. Once again, the Prime Minister overplayed her hand and unleashed violence against the protesters. A student political party, Chhatra League, allied to Hasina's party, Awami League, viciously attacked the protesters, sending many to the hospital; police shot at the protesters from helicopters. When I visited the country months later, the streets of Dhaka were filled with colorful murals made by students. One image I saw repeatedly intrigued me: a young man asking if anyone needed water. When I asked about it, my colleagues told me that a student had regularly brought the protesters water; he was shot and killed by the police, and later commemorated in wall art. In any case, rather than being intimidated, the protesters changed their tune, demanding that Hasina step down.

Autocratic rulers don’t like to be told what to do, so Hasina ordered the chief of the army—her own relative—to disband the protesters. He refused. Instead, he helped Hasina flee to India. India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, continues to harbor Hasina, despite demands by Bangladeshis that she return to the country to stand trial for her crimes—including murdering political opponents and protesters, and sending even the quietest of her opponents to the notorious prison called the House of Mirrors. In her absence, the founder of Grameen Bank, Mohammed Yunus, is acting Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

A side note: living in Dhaka, I made frequent trips to Thailand. Without getting into the intricate details of their politics, let’s just say that there were two main factions.

The Yellow Shirts, or People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) consisted of royalists, ultra-nationalists and the urban middle class, in opposition to then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, because of his habit of charging large bribes to approve business deals and his failure to sufficiently respect the King of Thailand.

The Red Shirts are formally known as the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) and were mainly rural workers as well as some students, left-wing activists, and others. They supported Thaksin who provided free third-class train travel and health care, even operations, to rural farmers and the urban working class (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-13294268).

I happened to be in Bangkok in May 2008 when the Yellow Shirts staged a week-long sit-in, occupying both the Bangkok airports to protest the Prime Minister. Thaksin ordered the police to evict them. The police refused. He then ordered the army to evict them. The army refused. Both the police and army refused to act with violence against their own people. The Yellow Shirts disbursed peacefully after a week and flights resumed.

I was again in Bangkok in April 2010 when tens of thousands of Red Shirts occupied two parts of Bangkok. (To give you a sense of just how crazy Thai politics can be, I saw a headline that read, “Yellow Shirts Claim the Pink Shirts are Red Shirts in Disguise.”) The Red Shirts occupied several streets and intersections peacefully, and were only attacked a month into their occupation. I was wandering the streets among the Red Shirts on April 10th; the next morning I saw the front page images in the paper of the bloody attacks on them by the army at their second location, resulting in the deaths of four soldiers and 17 civilians. Still, for the most part they were allowed to protest peacefully.

In both Dhaka and Bangkok, the lesson seems to be: if enough people are out in the streets, there is the potential that some of them are the relatives of those being ordered to fire on them, and the police and military might very well refuse.

But let’s return to Bangladesh. What does this messy story have to do with what is happening here in the United States?

First of all, 3.5% of the Bangladesh population of roughly 174 million would be about six million people. Nowhere near that number participated in the protests. But the protests were not one-off. The thousands of students who participated were out in the streets, day after day. After the first few weeks, they camped out, sleeping outdoors. They were not afraid of breaking the law or blocking traffic. They endured attacks by youth aligned with the government. They were shot at by police. Many were seriously injured, some were blinded, and hundreds were killed.

Nobody is asking people in the United States to demonstrate the courage shown by those young Bangladeshis. What they showed in courage, we need to show in our greater numbers. While they protested daily, for weeks, we need to protest regularly and find other ways to voice our disagreement, over months and years.

While the methods (and, I pray, the extent of violent reaction) vary, I hope that we can take heart from one aspect: the successful toppling of a regime, in part because one key pillar — the army — refused to go along with the demands of the authoritarian leader.

Again, what relevance does that have here?

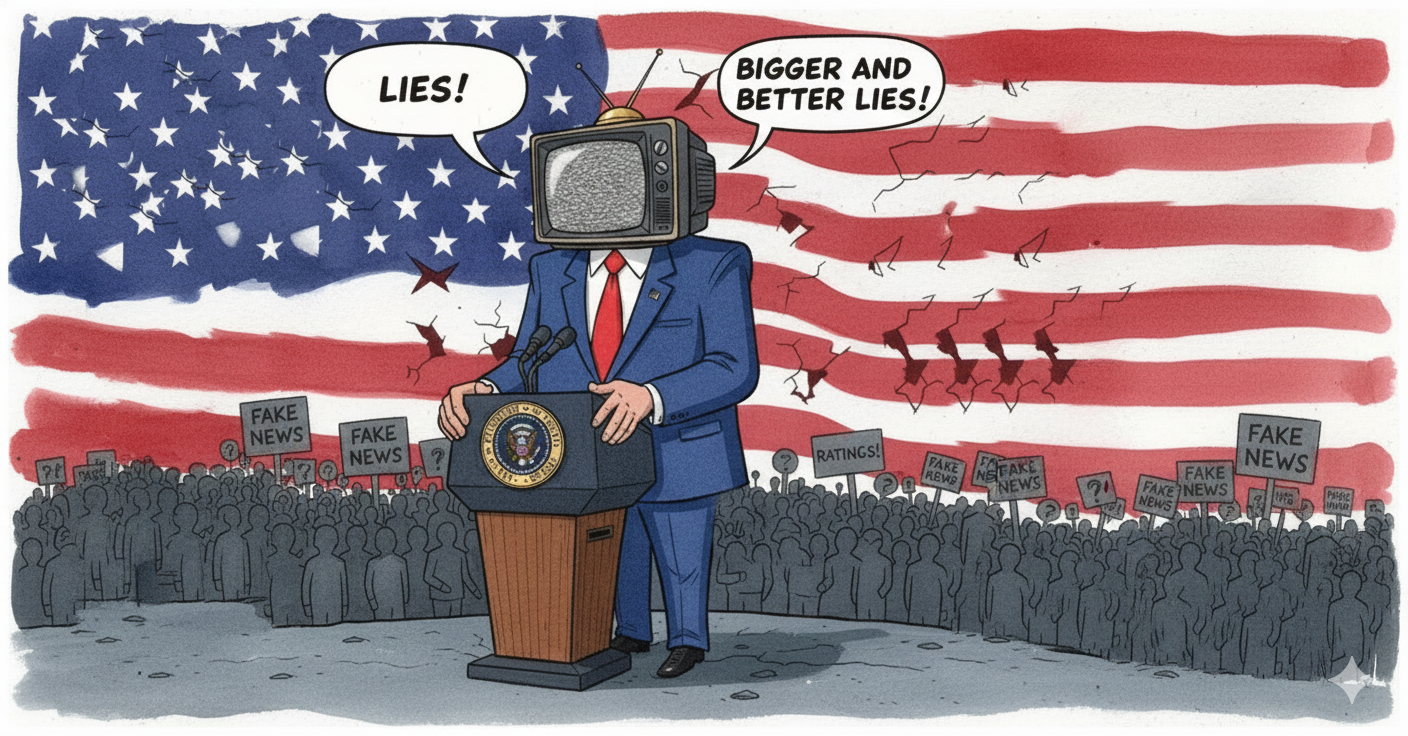

I’ve been reading about the demoralizing effect of calling out the National Guard and military in situations in the U.S. where they have no real role. We all watched and laughed at the obvious lack of enthusiasm of the army during the Orange Monstrosity’s pathetic military parade. There are reports that the 4,000 California National Guard troops and 700 US Marines sent to Los Angeles in response to the ongoing anti-immigration raid protests suffered from low morale (for example, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-06-24/veteran-advocates-low-morale-l-a-deployment). Neither have army personnel been amused at being asked to sit around or engage in meaningless activities just to show that Dear Leader is a strong man, despite all the evidence to the contrary (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/national-guard-marines-los-angeles-morale-pawns-b2769145.html).

There are cracks in the military pillar in the U.S. Those cracks can help topple a regime.

During most of those many years that Sheikh Hasina was leader, (1996-2001, as well as 2009-2024), I heard friends talk about going to their villages to vote in elections, only to be told that their vote had already been cast. I saw her government try to frame lead non-governmental organizations, raiding their offices and throwing their leaders into prison. I heard about her use of the Rapid Action Battalion—a visible presence on the streets—to murder her opponents. RAB allegedly dumped the bodies at the very cemetery where I would go jogging. One of my husband’s close relatives is still in prison, framed in a weird coverup involving an attack on the army that makes no sense (https://gpilondon.com/publications/the-unsolved-mystery-of-the-bdr-mutiny).

My colleagues and I took the lack of genuine democracy for granted and focused on the positives: the access we had to media and to government officials to push good policies through for health and the environment. We engaged in peaceful protest about issues, though never about politics (we wanted to be able to continue operating our NGOs, Work for a Better Bangladesh and the Institute of Wellbeing). We could not conceive of a downfall of the regime, and after all, the main opposition party did not seem much better (for example, https://news.abplive.com/news/world/bangladesh-hindu-attacks-awami-league-bnp-condemns-1786764).

In Bangladesh, following the toppling of the regime, there still have not been elections, and there remains plenty of unrest and dissatisfaction among the political parties and the people. Regardless of the outcome of overthrowing Sheikh Hasina, the youth of Bangladesh performed an enormous service to their nation and beyond.

They demonstrated courage in the face of repression.

They dared to imagine what others could not.

And they provided a moral compass, showing others what’s possible.

If they were willing to risk life and limb for the sake of their country’s future—seeing how those around them were getting beaten up, hospitalized, and killed—the least I can do is become involved in effecting change here, through the growing movement One Million Rising, to take power away from our current authoritarian regime and begin the necessary process of getting big money out of politics and returning power to the people.

None of that should take extraordinary courage. Are you with me?

A note on my sources: this information comes partly from the Web, partly from my conversation with locals, and partly from my own observations. I am also oversimplifying for the sake of readability.