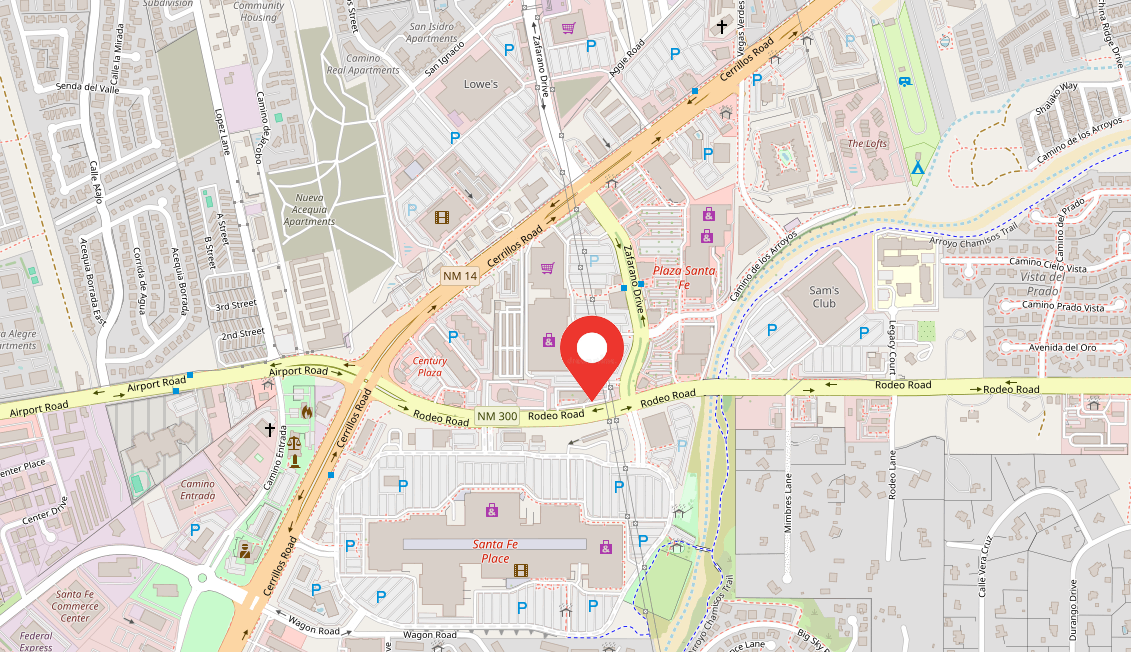

On January 3, Indivisible Santa Fe organized an emergency protest of the Trump administration’s military strike in Venezuela. We were able to rapidly turn out Santa Feans for a nighttime demonstration on the Plaza, urging that the US military get out of Venezuela and objecting to the use of military force to seize Venezuelan oil assets. We chanted, sang, and marched.

Such a demonstration was not the place for extended discussion of all the problems with the Trump administration’s actions. The wrongs are many and various: ethical, political, diplomatic, and legal. The legal ones are what I am going to discuss here. I aim to provide a sophisticated but non-technical overview.

The Bottom Line

The Trump administration's attack on Caracas clearly violated international law. The administration seems to be attempting compliance with domestic law, by relying on a law that gives Presidents the chance to use troops for armed force in another country and get Congressional authorization later.

Were Congress to conclude that Trump has already violated relevant domestic law or were Trump to fail to come into compliance, Congress could certainly use such violations as grounds for impeachment, but just as certainly the current Congress will not. The violations of international law will not have immediate consequences for Trump, Rubio, Hegseth, and others involved, however, they could have the gravest long-term consequences. The post-World-War II legal system famously makes individuals liable for war crimes like genocide. It also makes them liable for running roughshod over other sovereign states. The attack on Venezuela clearly invites United Nations sanctions, though the veto power enjoyed by the United States makes this practically impossible.

The problems with enforcing domestic and international law against Trump and others make it all the more important to understand just how flagrantly illegal their actions over the weekend were. No legal system works because it successfully punishes all transgressors. Legal systems create shared expectations about conduct, and many people comply with these expectations, and thus the law, out of a sense of conscience. Enforced penalties for lawbreakers can boost compliance by scaring others into law-abidingness as well as fulfilling retributive purposes. When enforcement and punishment is unlikely it is still crucial to record, share, and understand the legal wrongs committed. This serves to announce and articulate our expectations about acceptable and unacceptable conduct, even in the absence of enforcement. Moreover, by being crystal-clear about unlawful conduct we can create demand for real and robust enforcement mechanisms.

International Law

My colleagues at Just Security have an extensive write-up covering the international law violations committed by the United States attacks on Caracas over the weekend. Here are the highlights.

- “[S]triking Venezuela and abducting its president, is clearly a violation of the prohibition on the use of force in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. That prohibition is the bedrock rule of the international system that separates the rule of law from anarchy, safeguards small States from their more powerful neighbors, and protects civilians from the devastation of war.”

- “[T]he initiation of an armed conflict–triggering the application of the law of armed conflict, including all four Geneva Conventions–has meaningful consequences, ranging from the protections now owed to Venezuelan nationals in the United States, to the application of rules governing treatment of Maduro and his wife while in U.S. custody, to accountability for any war crimes committed in the course of the conflict.”

- “It is indisputable that drug trafficking is condemnable criminal activity, but it is not the type of activity that triggers the right of self-defense in international law. It is not a use of force, it is not “hostilities,” and it is not “combat,” despite Trump administration officials using these labels when describing drug trafficking activity.”

- “[B]ased on the U.S. position that all wrongful uses of force are armed attacks, Venezuela has the right to use necessary and proportionate force against the United States’ armed attack to defend itself…. Additionally, as provided for in Article 51 of the Charter, Venezuela may seek the assistance of other States acting in collective self-defense.”

- “[T]he U.S. action to remove Maduro as Head of State amounts to an unlawful intervention into Venezuela’s internal affairs …. Regime change by one State in another amounts to intervention when it is “coercive”…, which Saturday’s operation obviously was.”

- ‘[T]he United States has engaged in governmental activity in Venezuela–law enforcement–that is exclusively the domain of the Venezuelan government. … The United States claims, rightfully so, that Maduro’s presidency is not “legitimate.” … Even [so], international law provides that the relevant officials to grant consent are those of the government that exercises “effective control” … the Maduro administration…. Obviously, no such consent has been granted.’

- ‘[W]ithdrawing recognition of a government does not remove the personal immunity that the incumbent head of state enjoys under customary international law. Second, Rodriguez has said (post swearing in) that Maduro is “the only President of Venezuela,” and is calling for the release of Maduro and his wife.’

- “Even if international law permitted the United States to exercise enforcement jurisdiction in Venezuela, which it does not, the use of lethal force to do so was self-evidently unlawful. During law enforcement operations, resort to deadly force is lawful only when necessary in the face of an immediate threat of death or grievous bodily injury to the law enforcement officials or others.”

- “[U]sing force to acquire [nationalized oil operations] is unlawful, as the action does not qualify as self-defense, no matter how unlawful the expropriation may have been. And even if it did, the forcible U.S. action does not comport with the necessity condition for self-defense because there are non-forcible avenues that could be pursued.”

Domestic Law

The United States Constitution gives only Congress the power to declare an official war, see Article I, Section 8, Clause 11. Presidents have side-stepped this limitation on executive branch powers by claiming that their authority as commander-in-chief of U.S. armed forces permits them to insert U.S. troops into military activity even when no official war has been declared. This is how U.S. troops have ended up fighting in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, among other places. In response to Presidents Johnson, Kennedy, and Nixon putting U.S. troops in Southeast Asia without Congressional approval and without any official declaration of war, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution of 1973. This law specifically directs:

The President in every possible instance shall consult with Congress before introducing United States Armed Forces into hostilities or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, and after every such introduction shall consult regularly with the Congress until United States Armed Forces are no longer engaged in hostilities or have been removed from such situations.

Nobody from the Trump executive branch nor from Congress is claiming that there was any prior consultation between the Trump administration and anybody in Congress before troops were used to attack Caracas. Nor have I seen anybody claim that such consultation was not possible.

Notwithstanding this issue, the War Powers Resolution does have a mechanism whereby a President who has not consulted beforehand with Congress may retroactively seek Congressional authorization for military action the President has set in motion. If a President commits U.S. troops to action in the absence of a declaration of war or statutory direction by Congress, the President must, within forty-eight hours, report to Congress the use of troops, the authority under which they were operating, and various other specifics about the operation. This report is to be delivered by procedures and protocols detailed in the War Powers Resolution. Within sixty days, the President must remove all troops, unless Congress has declared war or statutorily authorized their continuing involvement.

So far, Trump has not made the required report to Congress. What he has done is threaten more military strikes on Venezuela, claimed the United States "will run" the country, and, through Secretary of State Marco Rubio, announced plans to continue the massive troop buildup in the Caribbean Sea. All this sets the stage for a violation of the War Powers Resolution, whether because Trump fails to make the required initial report to Congress, fails to get Congressional authorization for keeping U.S. troops in and around Venezuela for longer than sixty days, or both.