Like James Madison, the fourth President of the United States and Father of the U.S. Constitution who had misgivings about chief executives making religious pronouncements of any kind, I could easily dispense with the annual Thanksgiving Proclamation from the White House, or pardoning the turkeys. But still I enjoy the holiday and try to tolerate a little liturgical theater each November.

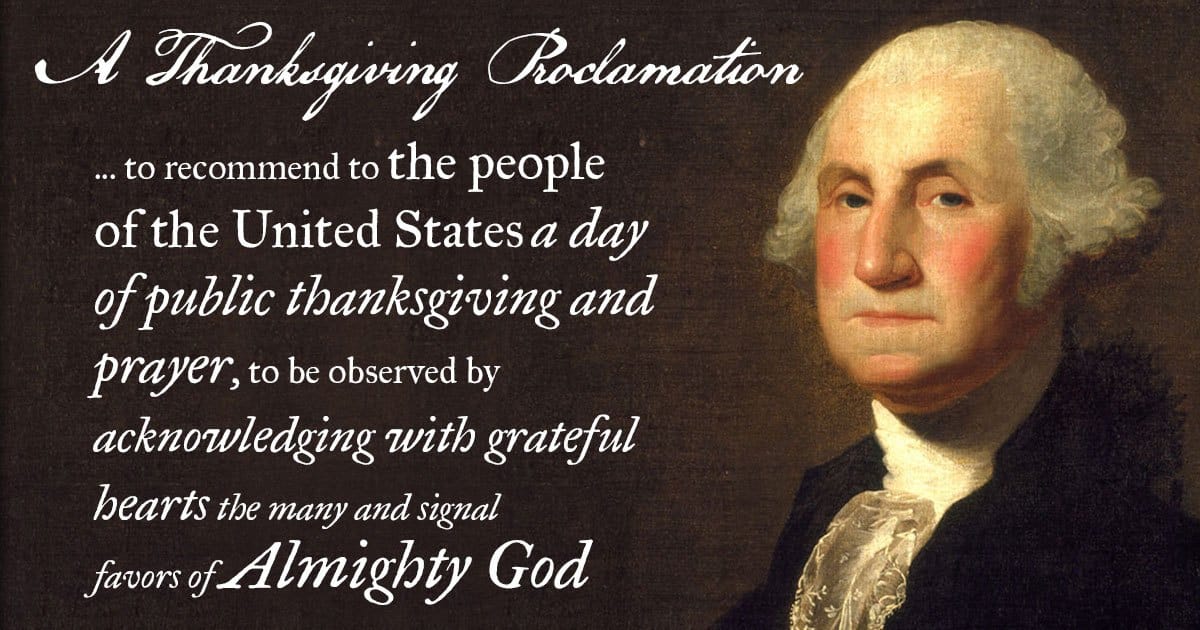

Glancing at George Washington's declaration of the first Thanksgiving, in 1789, provides an interesting window into the Founder's faith. He prominently offers gratitude for the "religious liberty with which we have been blessed." (Hurray for pluralism! Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians and Pagans All Welcome Here!) He also prays for the "practice of true religion and virtue, and the increase of science.” (Take that, climate denialism!)

Washington actually acknowledged "Almighty God" in this document, which was a rarity for him. More often, he referred to the deity with the kinds of circumlocutions that dot the rest of this Thanksgiving proclamation: "Beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be...Great Lord and Ruler of Nations...Providence." Interestingly, Washington nowhere, in any of his journals or correspondence, ever uses Christological formulas to refer to the divinity, e.g. Savior or Redeemer. In his own way, and in the context of his time, he was searching for what we'd now call inclusive religious language that went beyond sectarianism or Christian Nationalism to unite Americans of all spiritual persuasions in the bonds of fellowship, civic cooperation and goodwill.

Those frustrated by the current paralysis in Congress will note that George Washington's proclamation came just a year after the brand new Constitution had been ratified, replacing the dysfunctional Articles of Confederation. The new nation—where citizens were still more likely to think of themselves as Virginians or Pennsylvanians than as Americans—needed to pull together. Washington, and most of the other Framers, believed that religion could be a cohesive force, bridging the geographic, linguistic and political fault lines that characterized the country even then.

It was not a bad dream. And in today's polarized religious climate—when charges of anti-Semitism fly and Muslims are profiled as potential terrorists—the Founders remain a sensible model of how faith might yet become a link that unites rather than divides us from each other. I imagine even atheists might thank God—with a wink—for the First Amendment. So let's celebrate and offer gratitude this holiday:

For a world in which there are many faiths; For a nation in which there is still freedom of worship; And for a land where people of all creeds, colors and backgrounds can sit down together at the table of mutual care and respect.