New Mexico calls itself the Land of Enchantment, but for hundreds of souls swept up in Trump’s immigration dragnet, it’s becoming the Land of Enchainment.

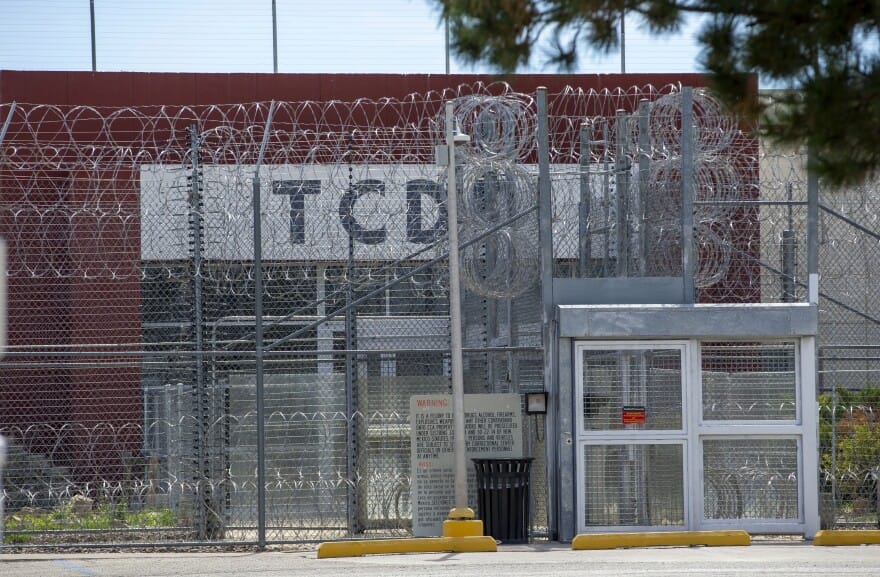

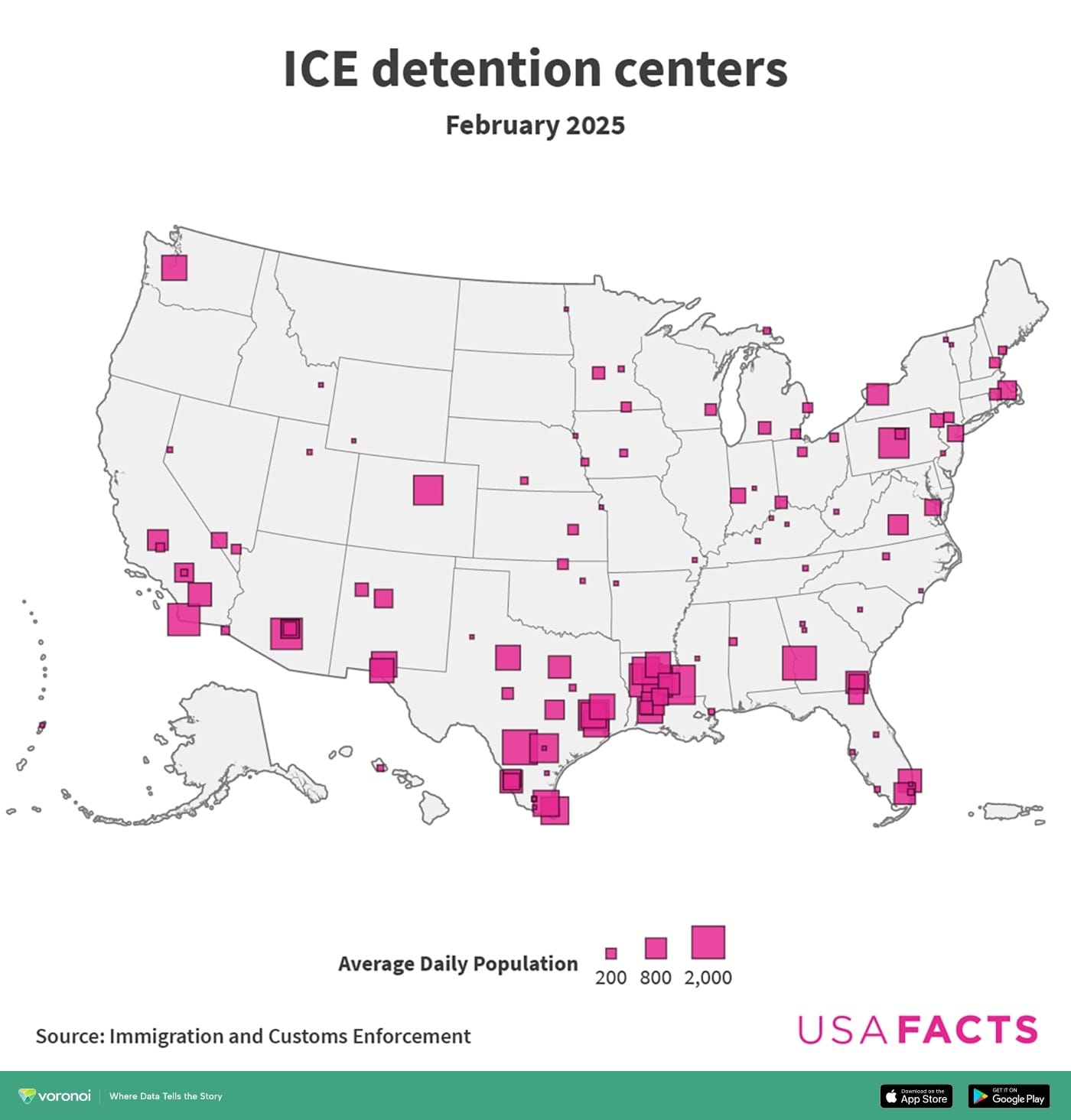

Recently I wrote about War Profiteers in the War on Immigrants, detailing how private prison companies like CoreCivic (which owns and operates the Torrance County Detention Center in Estancia, New Mexico) are capitalizing on U.S. government contracts to place soaring numbers of men and women behind bars. The so-called Big Beautiful Bill signed by Trump on July 4 will spend up to $45 billion in taxpayer dollars to keep people in lock-up. That's four times our annual state budget.

But who are the detainees, what are their stories, where did they come from, and how did they come to be living in America to be swept up by ICE?

Most have been living in the United States for many years. Roughly one third of the prisoners in the Torrance prison were apprehended more than 500 miles from here and are incarcerated far from their homes and families, according to Bloomberg News, which tells the story of John, transported half way across the country from his grandmother and his dogs in Florida while shackled at the wrists, waist and ankles.

His vision isn’t good right now; someone fell on him and broke his glasses while he was sleeping on the floor at an ICE facility in Miami.

Over the next few weeks, John will spend sleepless nights shivering in his cell. He’ll join an impromptu Bible study with other guys in his unit and watch the younger ones share their coats with older men during recreation time. He’ll eat in a room with a floor covered in feces. He’ll ask, many times, for supplies to clean it up. He’ll see a nurse for his back and his vision and his climbing blood pressure. He’ll receive nothing but Tylenol. He’ll participate in a hunger strike. He’ll watch men drink water out of a trash can brought in when the facility’s water is shut off. And he’ll gradually start to long to be deported to El Salvador, a country he barely knows, where he hasn’t lived since he was a child.

"Please truly, we need help from people from the outside," testified one prisoner who had to wait four hours for an ambulance to treat third degree burns he'd suffered in the kitchen where he worked, trying to make money for his family. "We're not animals, we're human beings."

Inside the grim walls of the Torrance County Detention Center, you may hear English spoken, but also French, Spanish, Arabic, Quechua, Farsi, Turkish, Portuguese and Swahili. That’s according to Cindy, a volunteer with Volunteers for Immigrants in Detention - Albuquerque (VIDA), a non-profit whose volunteers visit detainees in both Torrance County and at another ICE prison in Cibola County, near Grants, N.M. During a visit, Cindy said she met a young man from Afghanistan whose family members were killed by the Taliban. In fact, the prison is holding a number of men who served alongside U.S. forces and were then abandoned during the chaotic military withdrawal. Seeking safety in America, they were instead arrested by ICE.

Kesley Vial, who died in detention in 2022, is remembered by his friends as a hard worker, outgoing and playful. Born in São Paulo, Brazil, he grew up surrounded by the love and care of his grandmother, aunts and cousins after his mom emigrated to the U.S. Photos show an infectious smile, the kind you might want in a college roommate. Kesley came to this country as an asylum seeker but committed suicide after four months inside the Torrance County prison, unable to obtain any information about his case or when he might be released.

Officials in Torrance County have repeatedly renewed the contract with CoreCivic, which employs 93 people and is considered an economic boon to the impoverished community. But Gregory Hooks, a sociology professor who has researched and published on the prison industry, has documented how the prison-industrial complex actually impedes growth and development in rural areas, offering dead-end jobs and sapping money away from badly needed public services. In Torrance County, many of the prison jobs are filled by temporary workers, flown in from Houston or out-of-state.

Now New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham is considering calling a special legislative session to ban private prisons like CoreCivic from our state.

Please contact the Governor, today, asking her to end the abomination of ICE detention centers, like the ones in Torrance and Cibola counties, turning the Land of Enchainment back into the Land of Enchantment.

Write your own letter or cut-and-paste the following and send it to this link:

Dear Governor Lujan Grisham,

Please ask our legislators to pass a law banning private, for-profit ICE prisons from our beautiful state. Studies have shown that private prisons do not benefit local economies, but keep rural communities trapped in low-wage, low-skill jobs, rather than fostering real growth or opportunity. Conditions inside these detention centers are abysmal. Trump’s war on immigrants is already hurting workers, businesses and families in New Mexico. Without its prisons, ICE would eventually have to stop its campaign of harassment and mass arrests. Thank you for standing up for what’s right!