by Erin Daly*

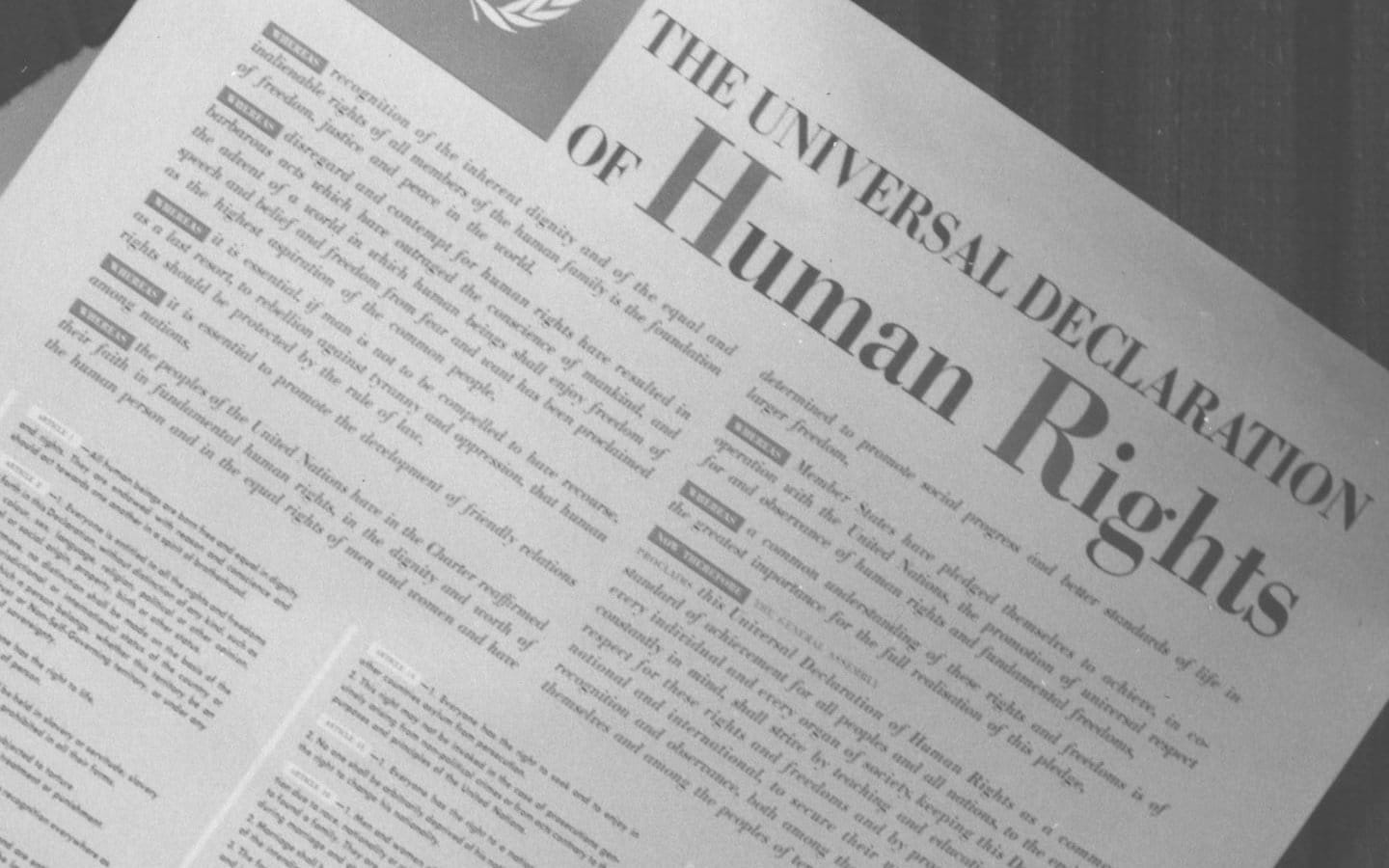

While the ashes of World War II were still smoldering, representatives from 50 nations came together in San Francisco and created the United Nations. The principal purposes were to “end the scourge of war” and to “reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights” and “in the dignity and worth of the human person.” One of the first things they did was establish a Commission on Human Rights and charge it with writing an international bill of rights: it was believed that “if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law” (as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would say). Hence, a rule of law for all the world.

But to insist merely on rule of law was problematic: the Nazi regime was governed by a system of laws. Laws were passed, officials enforced them, judges held people to account for violating them. They were evil laws, but they were laws. To distinguish the Nazi version of rule of law from the system they wanted to see, they chose an article of faith barely known to the law: “the dignity and worth of the human person.” In fact, they based the whole system of human rights on the simple the idea that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” This may well be one of the most profound ideas ever articulated in law – or maybe anywhere.

The idea that every human being has, from birth, the same value, the same worth, the same entitlement to rights as every other lays waste to any kind of superiority or supremacist ideology. To say that “all members of the human family” have equal worth is to reject social hierarchies based on gender, religion, ethnicity, or anything else. But assertion of equal dignity goes further. It does something that had never been done before: it denies to any person – or even any artificial intelligence – the power to judge the value of another human being: if we’re all equal, then no one can say that another human is less worthy, that one person’s life is less valuable. This goes to the heart of why Nazism, slavery, genocide, or any other form of oppression is wrong: all these ideologies are based on the idea that some people can decide that other people don’t deserve to live.

This, then, is what distinguishes law from justice: rule of law without dignity, like the legal regime of the Nazis, cannot be called justice. This is why the American Bar Association adopted a resolution in 2019 affirming “that human dignity — the inherent, equal, and inalienable worth of every person — is foundational to a just rule of law.” Dignity is not essential to formal rule of law, but it is essential to a just rule of law. Indeed, the ABA urged governments “to ensure that ‘dignity rights’ – the principle that human dignity is fundamental to all areas of law and policy — be reflected in the exercise of their legislative, executive, and judicial functions.”

A commitment to dignity is not based on evidence; it is based on faith, on the will to believe, on the ability to imagine a better world. It was the thing – to put it in quintessentially American terms – that the drafters of theUnited States Declaration of Independence were referring to when they said – contrary to their own established policies – that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” This was not reflected under law at the time, but they left us with the tools to bring forth a world that did reflect and protect it.

Despite this founding commitment, human dignity is not as entrenched in American legal thinking as it is elsewhere. But it is here. It has been mentioned numerous times in Supreme Court cases – most notably in cases involving claims about the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment, which the Court has said is about “nothing less than the dignity of man.”

It is this abiding belief that we can do better that is the basis of our faith that, no matter what America has done or is, we can always dedicate ourselves to the unfinished work of creating a more perfect union.

*Erin Daly is the author of Dignity in America: Transforming Social Conflicts (Stanford 2025).